Back in the day…

Back in 1987 I was consulting with a company that made aircraft galleys and other assorted aircraft interiors. The company was Nordskog Industries, and the owner – Bob Nordskog – had launched his company decades earlier (1951) when he learned that the demand for someone to make little kitchens for aircraft was paying high dollars for lightweight answers. He took a big risk and started this company. The process was very straightforward – figure out how to make one, then make some templates to copy all the panels to make more. Drawings? Don’t really need ’em. Quality? It’s good, isn’t it? It works, right? And we promise to repair it if it gets damaged. Nordskog did really well, and for a long time they were one of (if not THE) biggest makers of aircraft galleys in the U.S.

A company in the modern world that wants to compete in the global theater needs to use Lean manufacturing and Six Sigma as a starting point. Today, many companies use this as the goal. That is how far our manufacturing philosophy is out of sync.

DAvid west – “MAnufacturing 1987 style”

Along comes 1986 and the shifting winds of quality. Aircraft manufacturers start asking for more and more data – where are your drawings? How do you know the galley will survive a flight? What kind of defects are you seeing? How do you control your output? Nordskog was a family built business and the technology used to get consistent quality was the lead fabricator. He trained a few others who were pretty good, but the quality came down to these people. Six Sigma and the new ISO 9001 were becoming a problem for companies that made product by template and tradition.

I have a great respect for the folks at Nordskog who helped build that company. Dedication and care about the product was present everywhere. What was missing, and what really got in their way, was the ability to adapt. Nordskog was being told, by people who didn’t know them, how to do their job. Naturally they rankled, but they did their level best to follow along. Boeing came to them and asked for drawings for their galley. Since the tradition was to have the lead fabricator build the first galley based on the customer sketch, they did exactly that, then they handed the completed galley over to the drafters to make drawings.

Notice. The fabricator made the galley then handed it over to make drawings, so the drawings – when handed to the quality inspectors from the airline – would match the galley. Isn’t that what they asked for?

While the drafters were dutifully creating drawings of the galley, the fabricator was making the next galley. Some of the templates were ready, but not all, so the next galley didn’t quite match the first – but hey! It looks good, it works! The fabricator hands this galley over to the drafters.

Quality gets involved, They look at the drawings from the first galley, nice job. The drawings match the galley. They release the drawings. While the drawings are being released, the fabricator is finishing galley #2.

Notice. The fabricator has never seen the drawings, but is delivering the second galley.

Galley #2 arrives in quality, along with the newly released drawings. Guess what. The drawings (from galley #1) don’t match the galley (#2). The drafters get busy updating the drawings so the drawings match the galley and they can deliver galley #2. The fabricator is now almost finished galley #3 and wants to know what is slowing things down. He gets started on galley #4.

The quality team from the airline arrives, and they review the first galley (first article). Drawings match, very nice. Second galley and the drawings are delivered with all the accompanying deviations and Engineering Change Notices. Not so good, but the galley looks nice. Third galley. Doesn’t match galley one or two, but the drawings have been corrected to match the galley. Now the quality team has a conversation with Nordskog – you need to improve your quality.

Nordskog disagrees, of course. You asked for drawings for the galleys, here they are. The galleys are the same galleys we have been making since the 50’s – no worse. Lots of improvements, in fact. What could be the problem?

This was the chapter where I was brought into the company, along with another designer consultant. They needed some guidance to change their process so they would meet the quality expectations of the airlines. The company made investments in CNC routers, dedicated floorspace for fit checks and started weekly meetings. The one thing they didn’t change – they couldn’t change – was the culture around the fabricator. They knew that if they handed the fabricator the airframe drawing and the concept sketch from the airline that two weeks later the first unit would be finished. That culture, that undying knowledge that they had been running for decades without this fancy way of manufacturing, was immovable. In the end the company was unable to shift the culture and millions of dollars was spent in a blind alley.

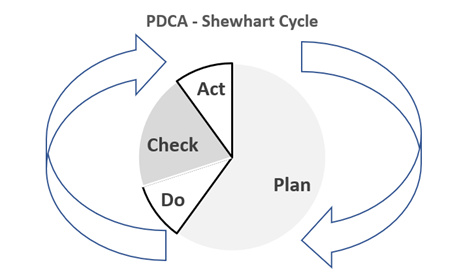

The problem Nordskog was hitting, being blindsided by, was the concept of intentional product development (aka “Design Engineering”) where the product is designed in concept, prototyped, verified and validated, piloted, and then put into production. Nordskog – not unlike a host of other companies, Porsche in the 80’s was another example – was focused on putting out the back door an example of what they can make as craftsmen. The manufacturing world was shifting more away from craftsmen and individual unit satisfaction to consistent results and performance. The PDCA cycle (often drawn as four equal sections, unfortunately) has three steps before “Act”. Plan – do the concept and design work; Do – make a prototype and start learning; Check – does the prototype meet requirements? Sometimes the “Act” part is to repeat the cycle because the “Check” showed failures. But in 1987, and in many smaller shops today, getting to the “Act” part is the number one priority.

Nordskog eventually suffered twin blows that ended the company – first a struggle with quality and manufacturing vs. craftsmanship, and then the death of Robert Nordskog in 1992. The good people at Nordskog moved on, and the company was absorbed by the shifting tides of industry. But to me, the lesson of transition is immensely valuable.

A company that believes the first successful unit they make should be sold and then they should try to make another has missed the end of the book. That book ended in 1945, but was slammed shut in 1986 with the introduction of Six Sigma. This is not to say Six Sigma is the crowned jewel – it isn’t. Six Sigma was just the introduction to the United States (and in some sense, the world) on how to compete with what Japan had found in the teachings of some engineers and statisticians. A company in the modern world that wants to compete in the global theater needs to use Lean manufacturing and Six Sigma as a starting point. Today, many companies use this as the goal. That is how far our manufacturing philosophy is out of sync.

I was reading some essays from “Gemba Walks” by Jim Womack, and one really struck true to me. He noted that in 1987 he was witnessing companies that were leveraging Lean techniques and methodologies and having such incredible success that it was apparent that this would catch on like wildfire and in a few short years would completely change the landscape of manufacturing (I am totally paraphrasing here – sorry Jim). In his note at the end of the essay he made clear that over a decade had passed since this observation. The wildfire had not caught, so many companies run exactly as they did in 1970. I have observed the same conditions – right down to the idea of having a form and a piece of paper accompany everything they do. Nothing wrong with paper but the ability to do any analytics is tough to do when the first thing needed is data entry that should have been done at the time of manufacture.

The world has moved forward in so many areas – SpaceX can land and reuse a rocket. The world is stuck in a bog in so many other areas – NASA is trying to find someone to manufacture their new rocket – the entire thing is designed to be used once and then fall to the earth. Worked for Apollo, right?